Prelude to D-Day

Britain is isolated and Moscow almost surrounded by the late summer of 1942. The grey countries are the neutral nations of Ireland, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and Turkey.

A first-time Canadian Army has

to overcome major early disasters to share centre stage in the Allied invasion of Europe called Operation Overlord.

September of 1942 was the high water mark of Hitler’s self-declared “Thousand-Year Reich”. The swastika flew unopposed from every continental non-neutral European capital except Moscow. But the Soviet capital was almost surrounded, under siege, and defeat seemed imminent; so imminent the Germans diverted their attention to more pressing matters — the southern Soviet oil fields. And so it was in North Africa as well, with Rommel’s Afrika Corps at the gates of Egypt, ready to push the British Army into the Red Sea. In less than three years, Germany had grown virtually unchecked into an empire larger than the Roman.

In stark contrast, September 1942 was the low ebb of Canadian army history. The Dominion had declared war against Germany exactly three years earlier, in September 1939, and mobilized hundreds of thousands of men and women for the mission. Yet the Canadian army's first two military ventures of this war — at Hong Kong and Dieppe, France — both proved egregious failures on both the Pacific and European fronts.

Germans in September 1942 gloated over their easy victory at Dieppe just weeks earlier in August. Newsreel footage of two thousand broken Canadian soldiers on a long march to German prison camps played in theatres across Germany. The black and white footage of dead Canadian bodies dancing in the tide at Dieppe was a feeble depiction of the reality — nine hundred Canadians had perished on the red-washed cobble shore. (See Dieppe on MLU.)

Meanwhile, halfway around the globe in Asia, over a thousand Canadian troops had been labouring in Japanese prison camps for almost a year by September ‘42, the remnants of a Commonwealth garrison in Hong Kong utterly destroyed by the “master race of the Pacific”. The Japanese attack had cost the Canadians 100% casualties by Christmas 1941. And in the Japanese prison camps, 1 in 4 PoWs would not survive their imprisonment.

So in its only two ground actions of the second war thus far, the Canadian units involved had suffered almost total destruction. Although both of these campaigns had been very enthusiastically endorsed by a government in Ottawa eager for its troops’ involvement, both campaigns had been British ventures, under British planning and co-ordination, prompting the usual Canadian navel-gazing into the relationship between mother empire and her colonial offspring.

In the Great War 1914-1918 Canada had fought as part of a British Army, fielding a full Canadian Corps, of four divisions, that was commanded by British officers until after the Vimy battle, when Canadian Arthur Currie took over command of the Corps in summer 1917.

1st Canadian Army formation sign, under which Canadians and attached units from other Allied nations fought.

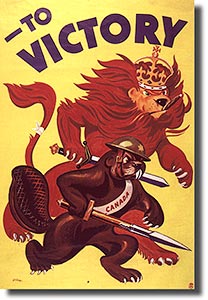

But by spring of 1944, as the invasion of Northwest Europe was about to unfurl, Canada was, for the first time in history, fielding its own army — the First Canadian Army — in which many British, American and other Allied units (Polish, Czechoslovakian, Belgian) were ultimately commanded by Canadian Generals, like Harry Crerar, Guy Simonds, and Charles Foulkes. In a quick about-face from dutiful dominion, Canada was suddenly a significant player in the Allied design for success on the European continent.

And so it was that in June 1944 the Armies of only three nations — the United States, Great Britain, and Canada — stood poised to shorten the life-span of the Thousand-Year Reich to six years, accepting nothing short of total victory over Nazi Europe.

*****

The story of D-Day & Normandy continues next page. ![]()

If you have any observations, comments, insights, or see any errata, typos please Contact Us.